At the beginning of April 2022, New York State approved a budget that included $600 million for a new football stadium in Orchard Park for the Buffalo Bills.This sparked criticisms and celebrations, with both sides arguing what value should be put on keeping a professional franchise in a particular city. Why should the public be spending hundreds of millions of dollars to subsidize a billionaire owner and one of the wealthiest leagues in the world? Why would we risk losing a franchise that is seen as a fundamental part of our community? Is there a better balance that we can strike?

I’ve written about how stadiums relate to the cities they’re in before on this blog, primarily focusing on baseball stadiums (surprisingly the sport with the most urban beginning). But I want to take a larger view of the discussion and how we might find a better way to keep our teams in the cities they have come to be synonymous with.

No one can question that being considered a “major league city” has a certain impact on the pride of a community. Having your skyline broadcast across the country and hearing your city’s name discussed alongside other cities who may be much larger or more prominent than your own helps boost a sense of pride among citizens, even those who are not fans. As Dan Moore put it in an article for the Ringer, “They remain perhaps the last public-private institution capable of transcending partisan divides at scale, and they inspire a kind of devotion that few enterprises can match.” And that is a powerful force. Providing a common theme to unite around and hold up as a symbol of your community is an intangible benefit that is hard to put a price on. While this discussion is primarily on professional sports, college sports can have the same (if not even a more robust) effect on the communities they reside in.

These teams come with many side benefits as well, including team sponsored foundations that support education, health, and athletic programs, often in disenfranchised communities. Just one of many examples is NYCFC building over 50 mini soccer pitches across New York City to help provide open space and athletic opportunities to kids in each of these neighborhoods. Teams can also attract other quality of life amenities such as musical performances, museums, and art shows as the City now has a raised profile across the country. These artistic scenes can, and do, thrive without a major league franchise, but there is a long history of athletes connecting with and promoting artists in their cities, giving them a reach they may not have been able to achieve on their own.

But these cultural benefits can also provide a team, and specifically their owner, with an incredible amount of power.

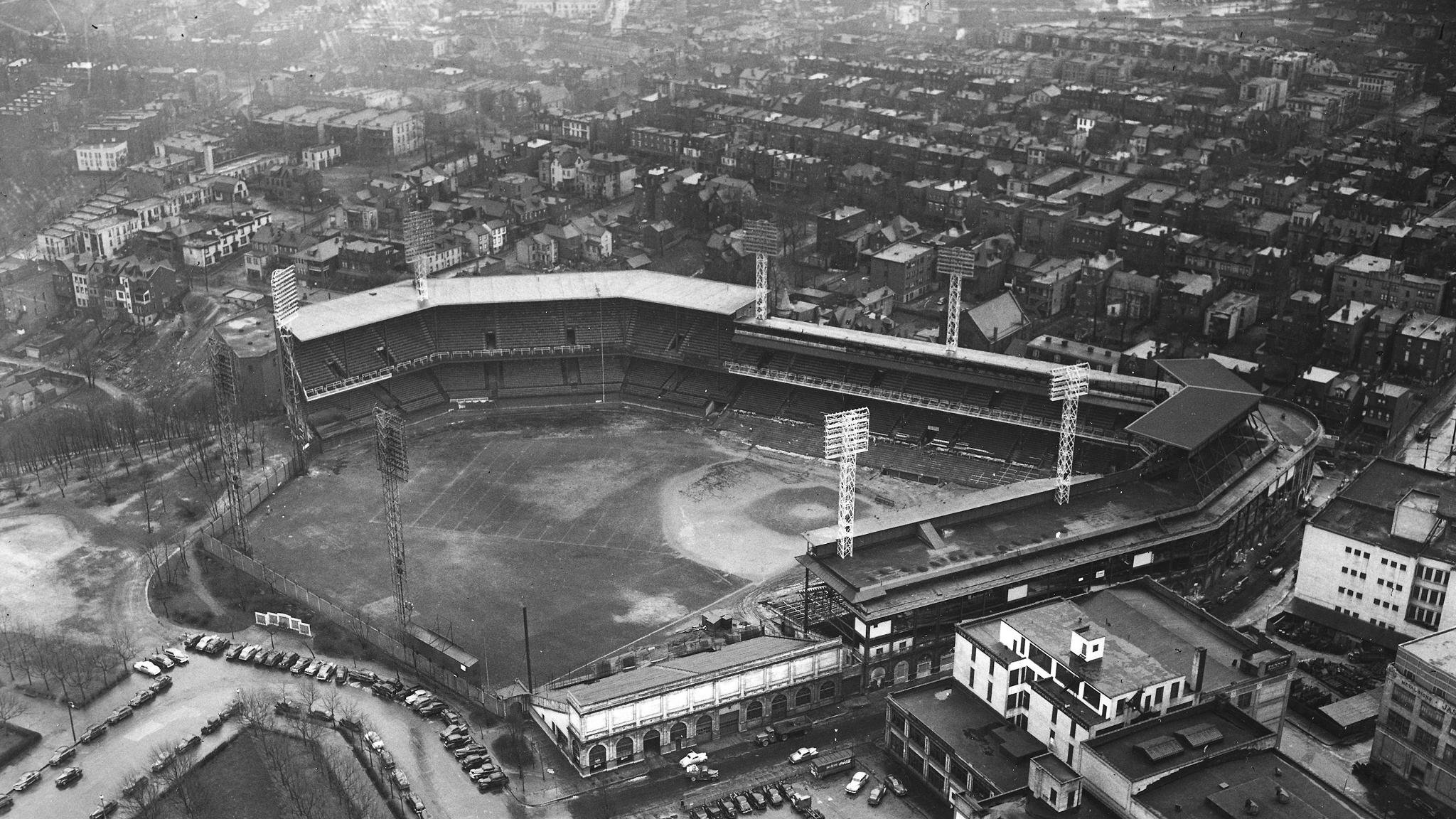

It is true that it’s tough to imagine Buffalo without the Bills, but at one point it was impossible to imagine Brooklyn without the Dodgers too. There are dozens of examples of teams leaving cities to seek out a higher profile or a better financial deal, and for the cities they leave behind it can be a true blow to civic pride and engagement. As Aaron Cowan wrote when discussing the major shifts in baseball during the urban renewal period of the ‘50s and ‘60s, the “…loss of a professional sports franchise amounted to a tacit admission that a city was dying.”

This mentality still rings true today. To lose one of your greatest promotional tools is a blow to a region, and the owners know it. Since the 1950s, teams have been using this power to their advantage in acquiring funding for new and improved stadiums, or extended tax breaks for renovations, all while gaining incredible wealth off of the talent of their players. They have continually threatened to leave cities if they weren’t given sweetheart deals on land to develop or, in what is increasingly the case, provided extreme amounts of public funding to support their for-profit businesses. And this is on top of evidence that these investments do not financially pay off in the long run, especially football stadiums.

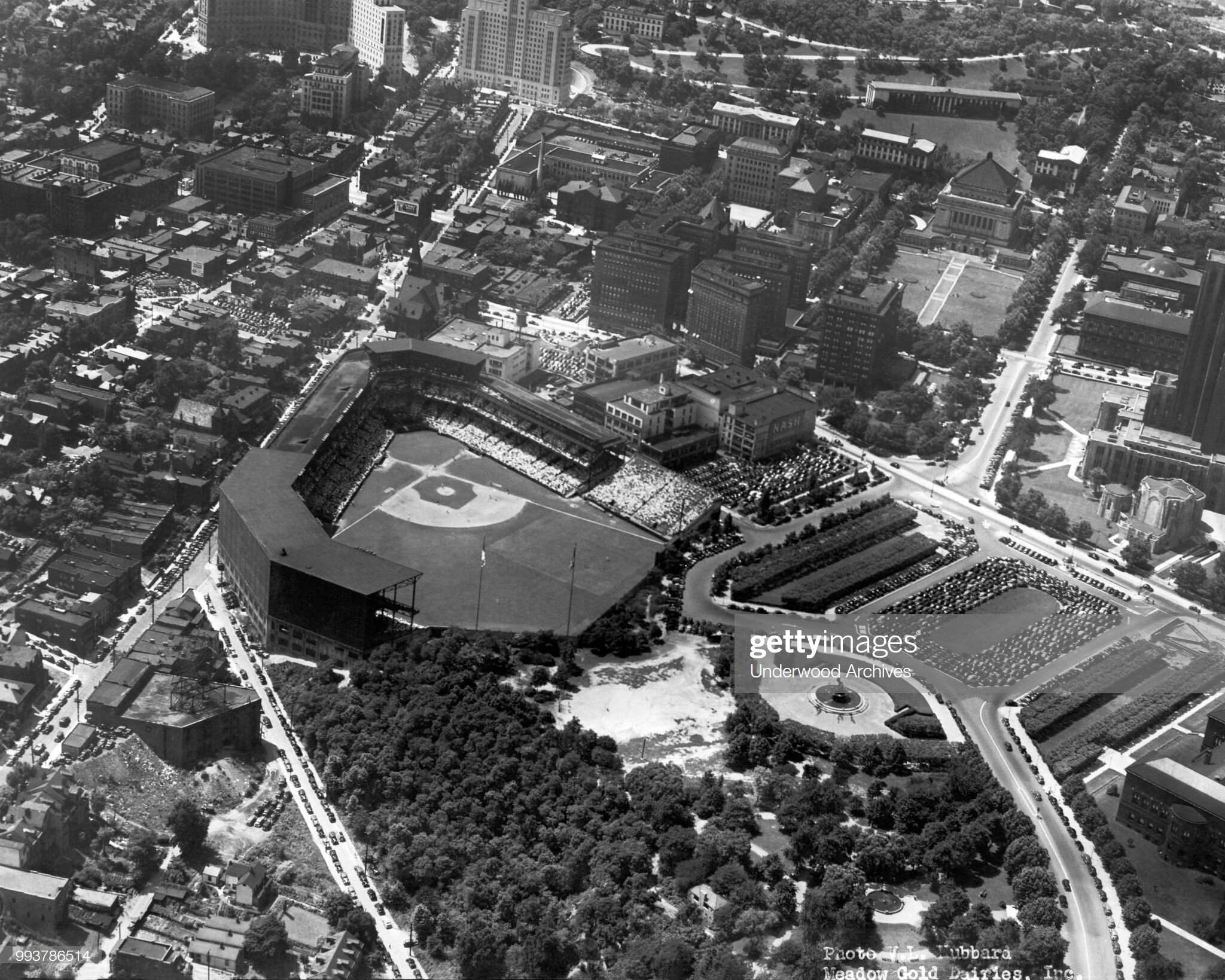

New Yankee Stadium was developed with public assistance through the transfer of park land.

The New York Yankees were given park land for free to develop their new stadium and large tax deductions in tow, with the only requirement that they convert the old field to a park when it was torn down.Las Vegas put up $750 million to construct a $2 billion stadium for the Raiders, which was a prerequisite for attracting them to the city, slashing the area’s education budget to chip in. The Buffalo Bills stadium will receive a total of $850 million in taxpayer funds to build a $1.4 billion stadium across the street from the old one. While a Downtown Buffalo stadium was explored, the extra cost was deemed too steep, even if that location would provide additional development/economic opportunities and be far more accessible to all residents as it would be located near several bus lines and the light rail line.

While I won’t say the public should not invest to some degree in these facilities, as there truly are benefits to having a major league team, what has now become expected of cities (funding huge portions of these projects with little benefit beyond keeping the team in town) is unacceptable. If a team receives public investments in their projects, they should be expected to do more with that money than simply line their pockets.

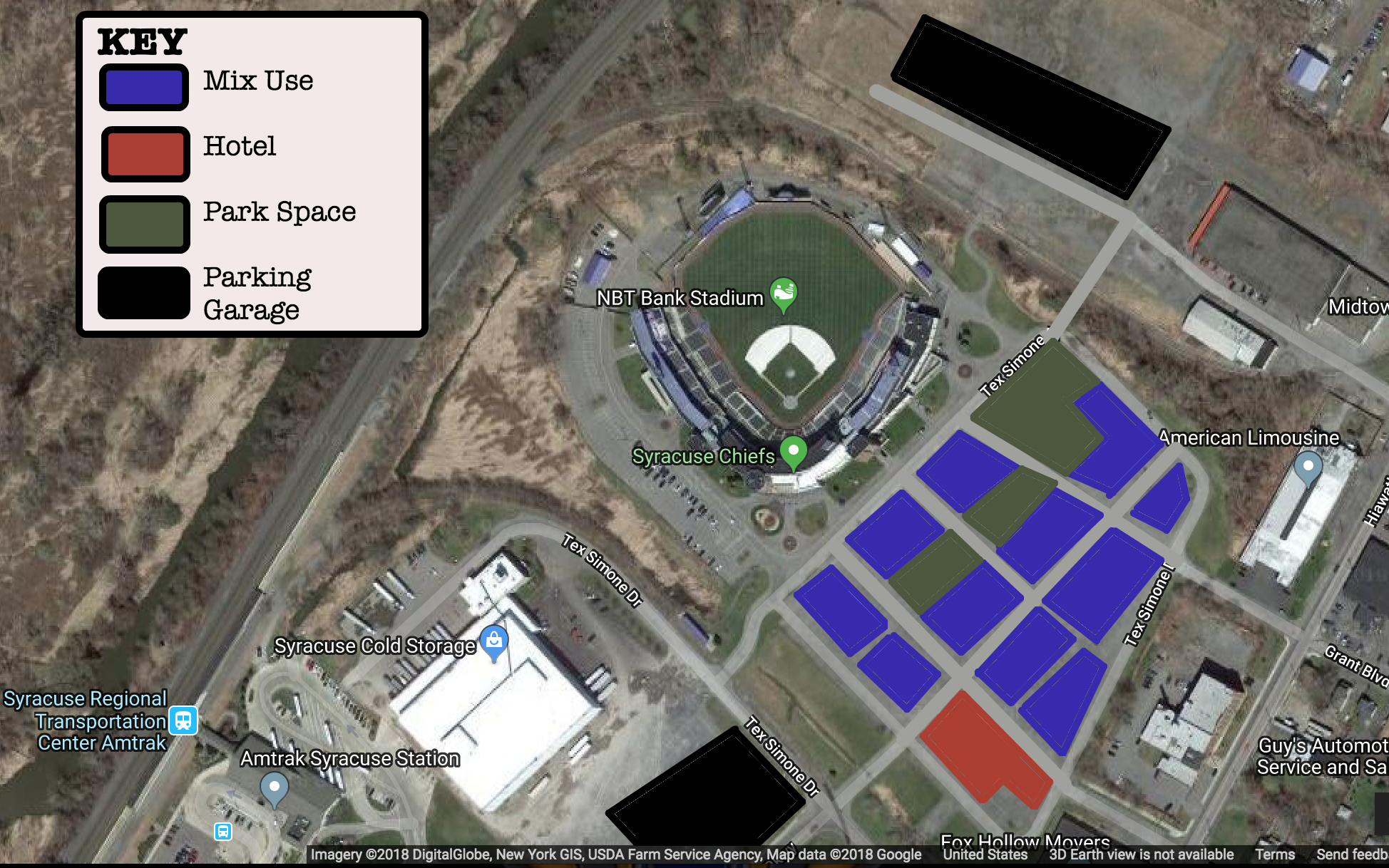

Using NYCFC again as an example, the team’s current search for a suitable location for a soccer specific stadium includes the goal of providing hundreds of units of affordable housing in an adjacent development, along with retail and office space, helping to create a dense, mixed-use neighborhood. Housing affordability is a long-term crisis for New York City, so to have an MLS team include hundreds of units within their development plans only makes sense. Other cities should consider this requirement as part of stadium developments as well, but this brings up the discussion of where these developments should take place.

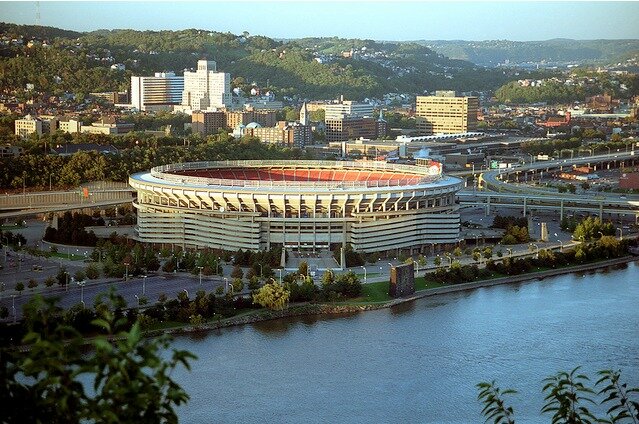

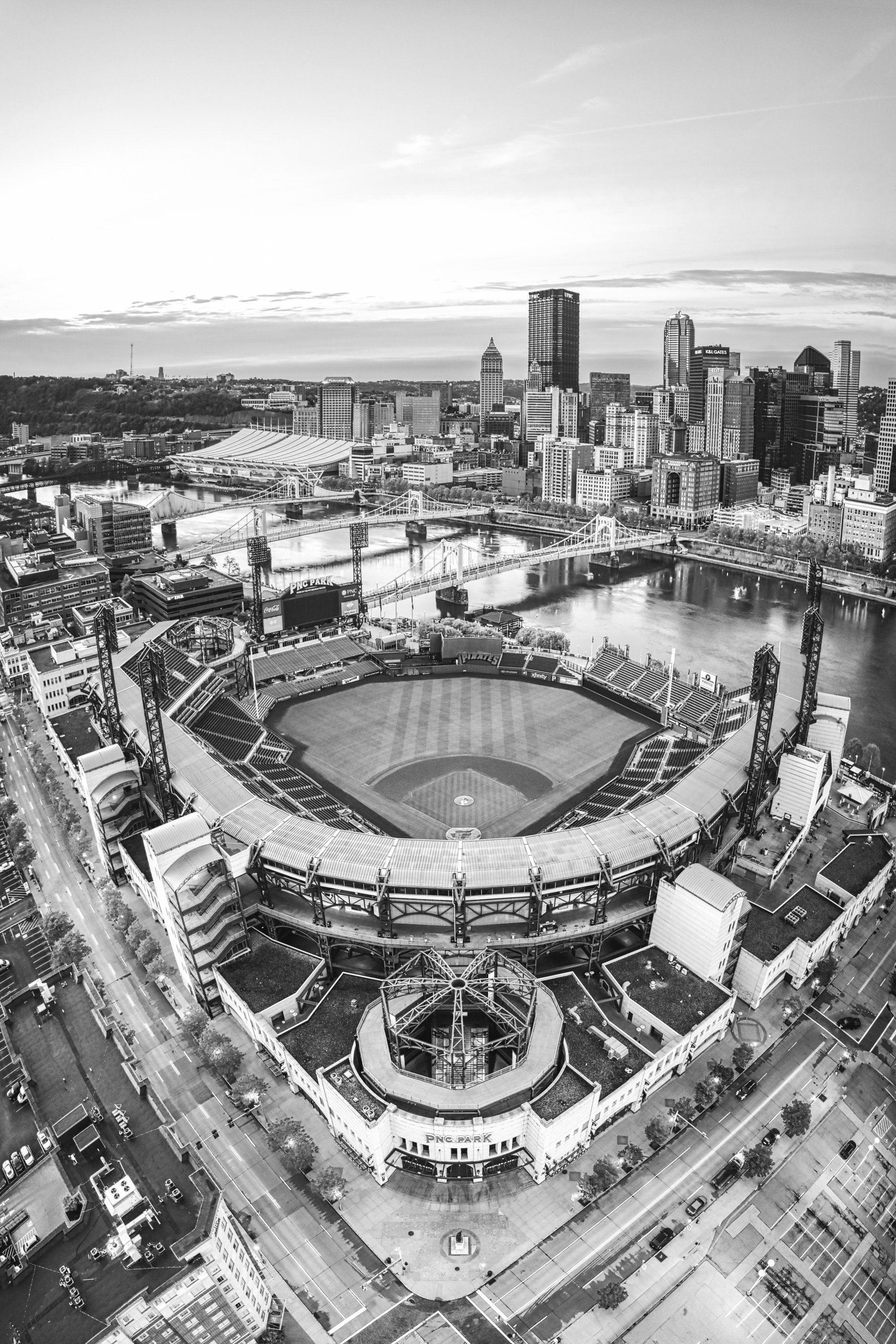

PNC Park, home of the Pittsburgh Pirates, sits across the river from Downtown Pittsburgh and is surrounded by restaurants, bars, and park land.

While we want to make sure any sort of stadium development does not displace residents or businesses as much as possible, we should be asking that these developments occur close to the urban center. By locating near the urban center, and reducing the size of the typically massive parking lots, you increase the accessibility of the stadium by non-car transportation modes, which is beneficial from an environmental stand point but also increases the ability of households without personal vehicles to attend games and events. The central location also benefits any affordable housing or commercial development associated with the stadium. Residents would enjoy access to public transit and shorter trips to work/shopping while businesses would benefit from an accessible location and association with their city’s team. You also benefit the businesses already in the neighborhood by bringing in additional customers during game days. Suburban stadiums are often surrounded by seas of parking lots with nothing around them, while urban stadiums encourage visits to nearby bars, restaurants, and retail locations.

Even if we do work out deals where team owners develop their stadiums in easily accessible urban locations and provide affordable housing/commercial development spaces alongside them, we still should not have public entities picking up the majority of the bill. Owners are billionaires with plenty of money to play with. If they require the public to put up substantial sums to subsidize their own wealth, cities/counties/states should be able to take partial ownership of these teams as they have invested in the teams as much, if not more, than the owners have. The development of a true public ownership model (most likely through a public-private partnership that leaves the team out of the day-to-day concerns of our elected officials) is beyond what I will discuss here, but its something that should be explored more if the public is continually asked to foot the bill for these large construction projects.

Hosting a major league team, or a high profile college team, does come with some powerful benefits; raised profile, increased civic pride, economic development opportunities, etc. But we cannot allow their owners to strong arm our cities and regions into subsidizing their profits. We need to ensure these stadium deals provide real benefits to their communities and give the public more of a say in what they entail. Teams are a quasi-public entity and we should try to make them more of a public benefit.

The new roof to the Carrier Dome, the most visible part of a $250 million renovation project that was primarily privately financed.