Over the course of four months, as part of an eight member team, I helped produce an in depth look at how bike lanes and pedestrian improvements could benefit a corner of New York City that is often overlooked when it comes to transportation projects. Tucked away at the far eastern border where Queens meets Nassau County, Community District 11 (Auburndale, Bayside, Douglaston, Douglas Manor, East Flushing, Hollis Hills, Little Neck, and Oakland Gardens) often shares much more in common with smaller cities across the country than with the rest of New York City. Nearly every family has access to at least one car, and those who travel by public transit are primarily using the bus. Beautiful parks and green spaces populate the area, and most homes have small backyards for kids to play in. These are scenes you don’t associate with the largest city in the country, yet here it is.

Our eight member team, assembled as part of the Planning Studio requirement for attaining a Masters in Urban Planning from CUNY Hunter College, took on the task of bridging the gap between the community and NYC DOT with hopes of bringing needed improvements to the area’s transportation network. While I don’t wish to get into the details of the plan (which you can read at the link below), I look to briefly reflect on what was learned through this process.

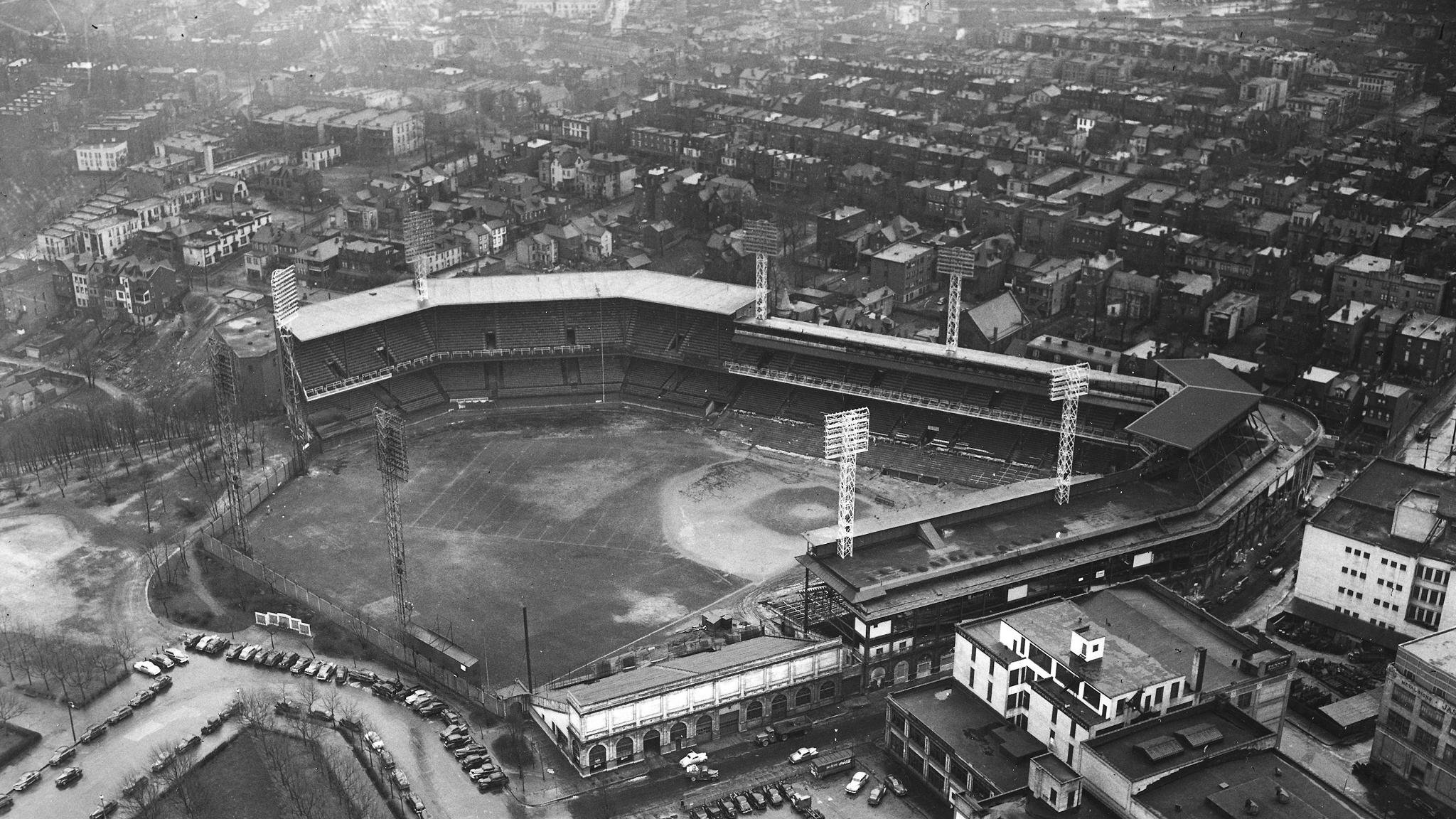

A protected bike lane along Northern Boulevard. The implementation of this needed infrastructure caused a rift between the community and NYC DOT.

There Is Space for EvERYONE

American cities have continually overbuilt our roadways, especially on the local level. While this has become a common place notion among planners over the course of a few decades, we still have not fully grappled with how to repurpose this space and do so without making communities feel as though they are losing something. This doesn’t mean that a bike lane should be placed on every street with excess space. It doesn’t even mean that we always need a bike lane to begin with.

During our outreach to the public and our in person observations, we came to realize that many streets within the neighborhood are already safe for riding bikes, even without infrastructure there. This is the case for countless neighborhood streets across the country where only residents drive and usually at very slow speeds as they approach their homes. These are the streets millions of kids learn how to ride their bikes for the first time. By acknowledging this to the community we also gained their trust that we weren’t going to be putting infrastructure where it wasn’t needed. We made clear that only wanted to intervene where it was important to improve safety or help direct riders.

Old in Body, Young at Heart

We were continually surprised at the number of people over 65 who ride bikes everyday, including an 86 year old man who rides his bike everyday. It was a good reminder that all spaces should be accessible to all ages. While I continually find myself considering how children interact with spaces, primarily due to my background of working in schools, those same considerations should be shown for our aging neighbors. Just because they are getting older does not mean they don’t plan on staying active within their neighborhood. Positioning bike infrastructure and pedestrian improvements as a way to encourage a more active lifestyle and improve safety can be one way to encourage a conversation about how we interact with our environment.

Stay Involved

One of the most important decisions our team made was to stay in active contact with the local transportation committee. While our client may have been the DOT, we knew that we needed to be even more involved with the community. By showing up to meetings, reaching out for conversations, and staying in touch, we were able to bring our plan to the community and have a real discussion about our report. They may not have agreed with everything in our final report, but they found many proposals that they were interested in pursuing. We continually emphasized that the purpose of our plan was to start a conversation, and now the community and DOT have a common point of reference to work from.

While we always wish that we could’ve contacted more residents and gained even more insight into the needs of the community, we believe our commitment to involving the committee members throughout helped shape our plan in a tangible way. And while I cannot speak for every member of our team, I do believe that many of us would be happy to continue fielding questions about the plan proposals and findings to help the community move forward.