Browse through articles dealing with urban planning or urban policy and you will continually come across terms such as “Superstar City,” “Cities of Relevance,” “Rust Belt,” etc. Each of these terms, while meant to describe cities of a certain nature, impact how people see the communities in which they live. More often than not, when coming from a city in Upstate New York, these terms offer a negative view of where you have spent your life. At the same time, those living in these so-called “Superstar Cities” have been left wondering why there has, at times, been an antagonistic view towards them. While there are many reasons for the divides within our country, the terms urban planning writers have decided to use to describe cities has only helped to further an us-versus-them mentality. We need to find better ways to describe the differences within cities without trashing some and elevating others.

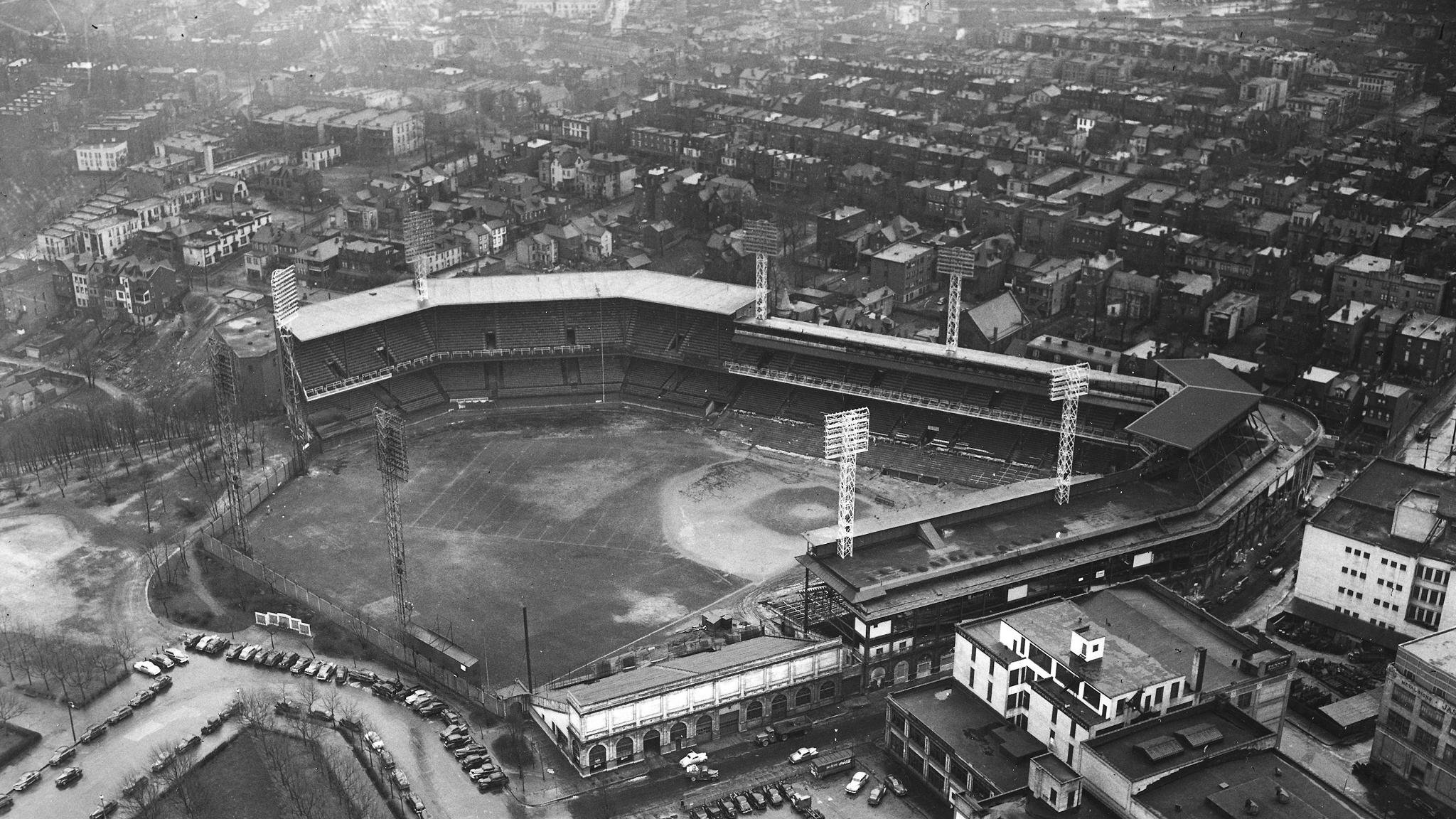

Richard Florida is credited with creating the term of “Superstar City,” primarily to describe large metropolitan areas that have robust financial resources and are often linked closely with other commercial capitals throughout the world. But this is not the only term used to elevate these cities over others. Throughout my education I have also come to hear these cities described as “Cities of Relevance.” This term, more than any others, has frustrated me. By describing cities in this manor you have determined that the majority of cities, where the majority of people live, are irrelevant. While I understand that many smaller cities, including my hometown of Syracuse, do not have as close economic ties to international hubs as others, to write them off as irrelevant is a simple way of sewing resentment within these communities.

You don’t have to look too hard to find people or organizations that believe these larger cities have made it worse for their communities, even when the opposite may be true. New York State offers a perfect example. New York City is the economic heart of the state, generating immense amounts of wealth and taxes that help support the rest of the state. At the same time, many communities in Upstate New York feel as though their voices are not being heard and their problems are being ignored in favor of Downstate priorities. Downstate residents often do not understand, or appreciate, the economic issues facing Upstate communities, a fact that I have routinely run into while living and studying in New York City. Both communities simply see each other as the problem, often because they have continually been labeled in ways to pit them against each other.

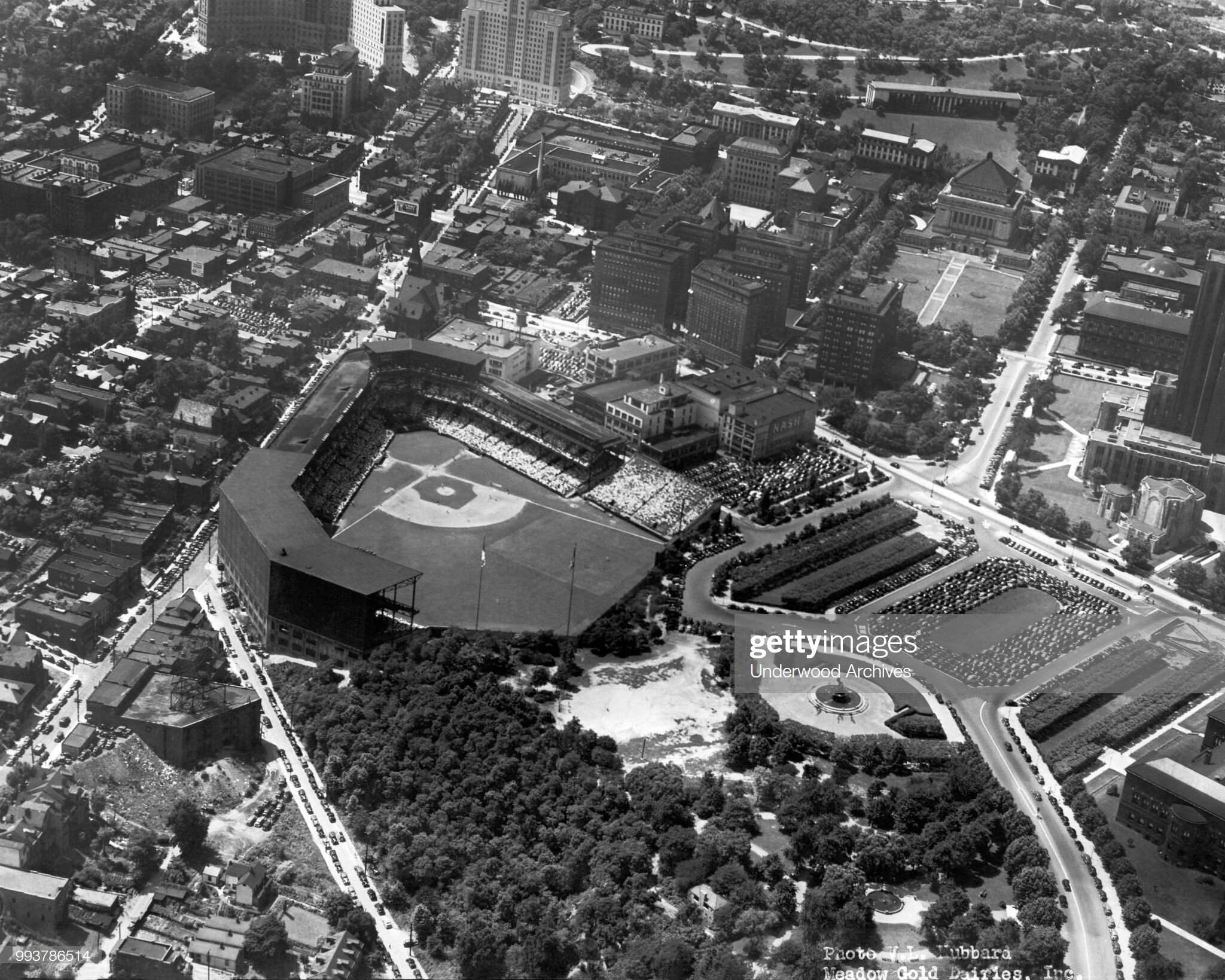

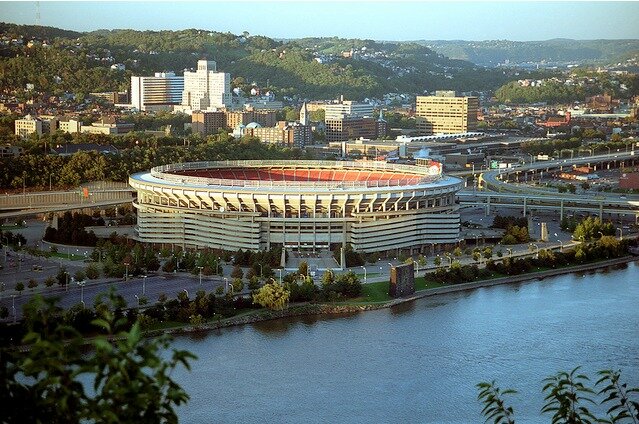

This us-versus-them mentality can be seen on the national scale as well, with many communities in the Midwest and the Great Plains feeling forgotten, often due to being referred to as “Flyover Country.” And yet, many discussions on urban planning and policy being had in the major hubs on the coasts, often forget to mention, or simply write-off, the problems faced by these smaller cities. They then wonder how it is that voters in these same communities vote in ways counter to how these “Cities of Relevance” believe they should.

Having lived in cities labeled as both relevant and irrelevant, I do not believe our current terminology is benefitting anyone. Elevating cities to “Superstar” status leads to a mentality that their concerns should be prioritized over others. This is foolish when considering that most people do not have the opportunity to choose where they live and work. What zip code you are born into has been shown to determine what type of access you will have to opportunities throughout your life. Instead of elevating cities over one another, we should be looking to embrace their unique qualities and find ways to connect them. Yes, we will need terms to discuss the differences between cities, both economic and culturally, but we should be looking to use terms that look to clarify differences, not make a value judgement.