Downtown Syracuse, like so many other downtowns across the country, is considered one of the most walkable places in the community. Wide sidewalks, frequent crossings, stores, restaurants and bars, and varied architecture throughout help make it an inviting place to walk around and enjoy the day. Even with so many of these factors favoring walkability, it is impossible to ignore that cars remain dominant within the neighborhood.

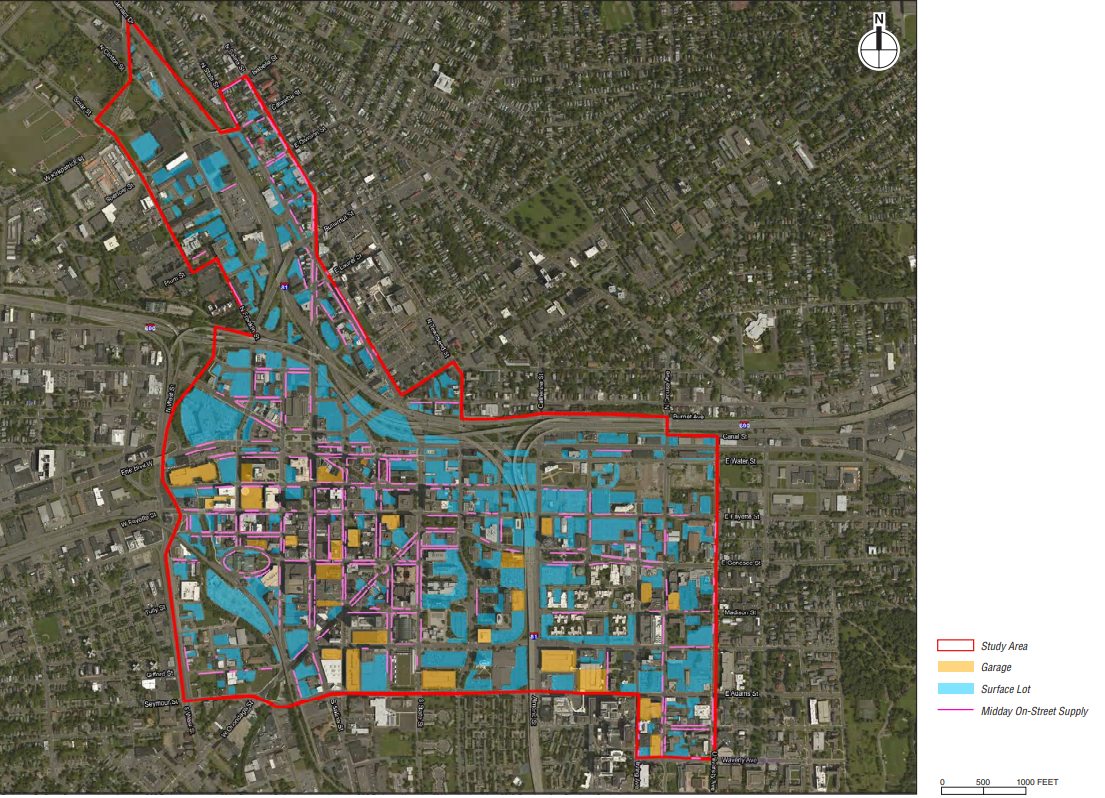

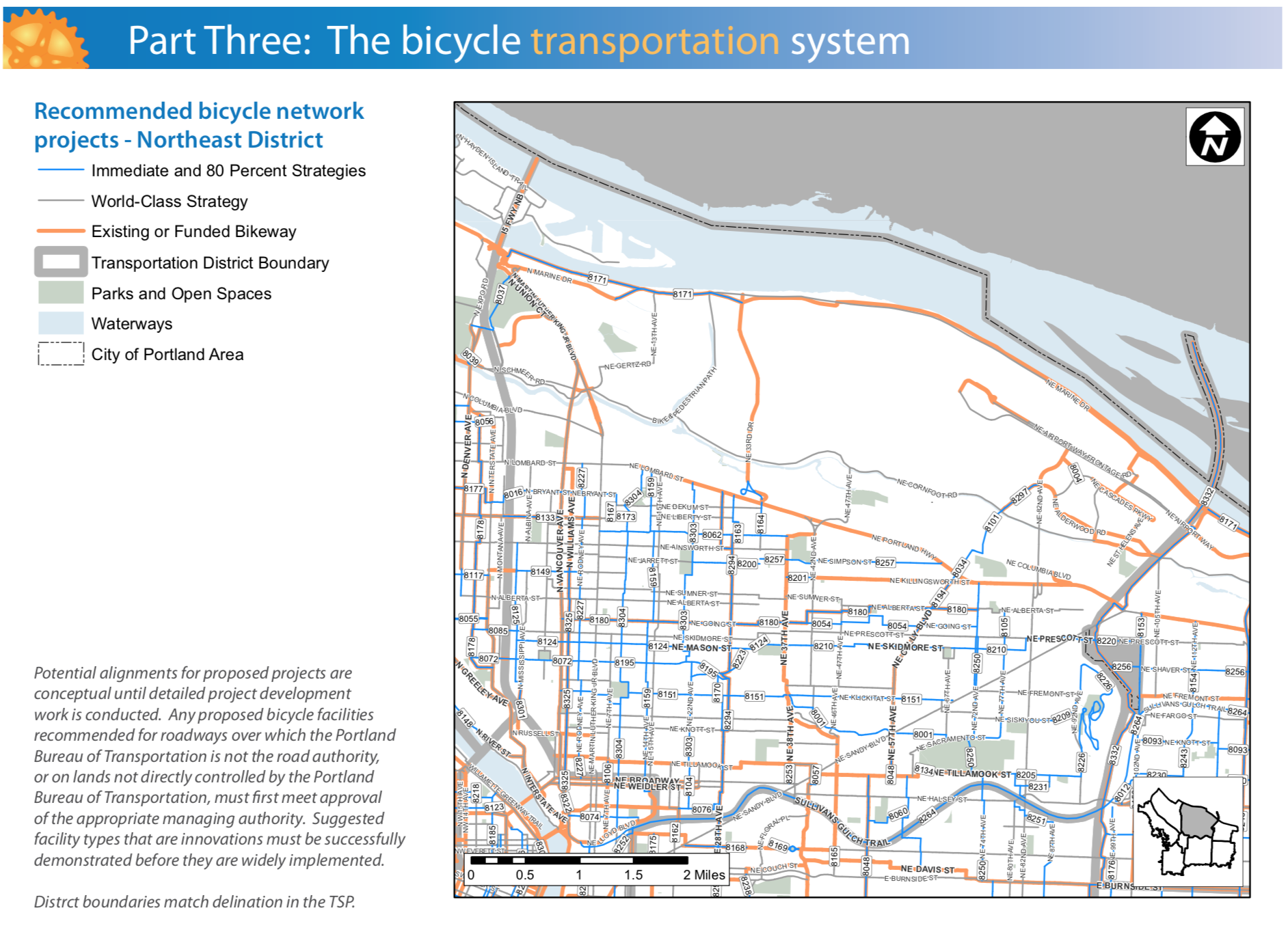

First, let’s begin with the obvious - Downtown Syracuse is an island surrounded by parking. Chapter 5 of the Preliminary Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the I-81 construction project showcased the map below which identifies all of the parking structures in and around Downtown Syracuse.

Parking infrastructure map from the I-81 PDEIS

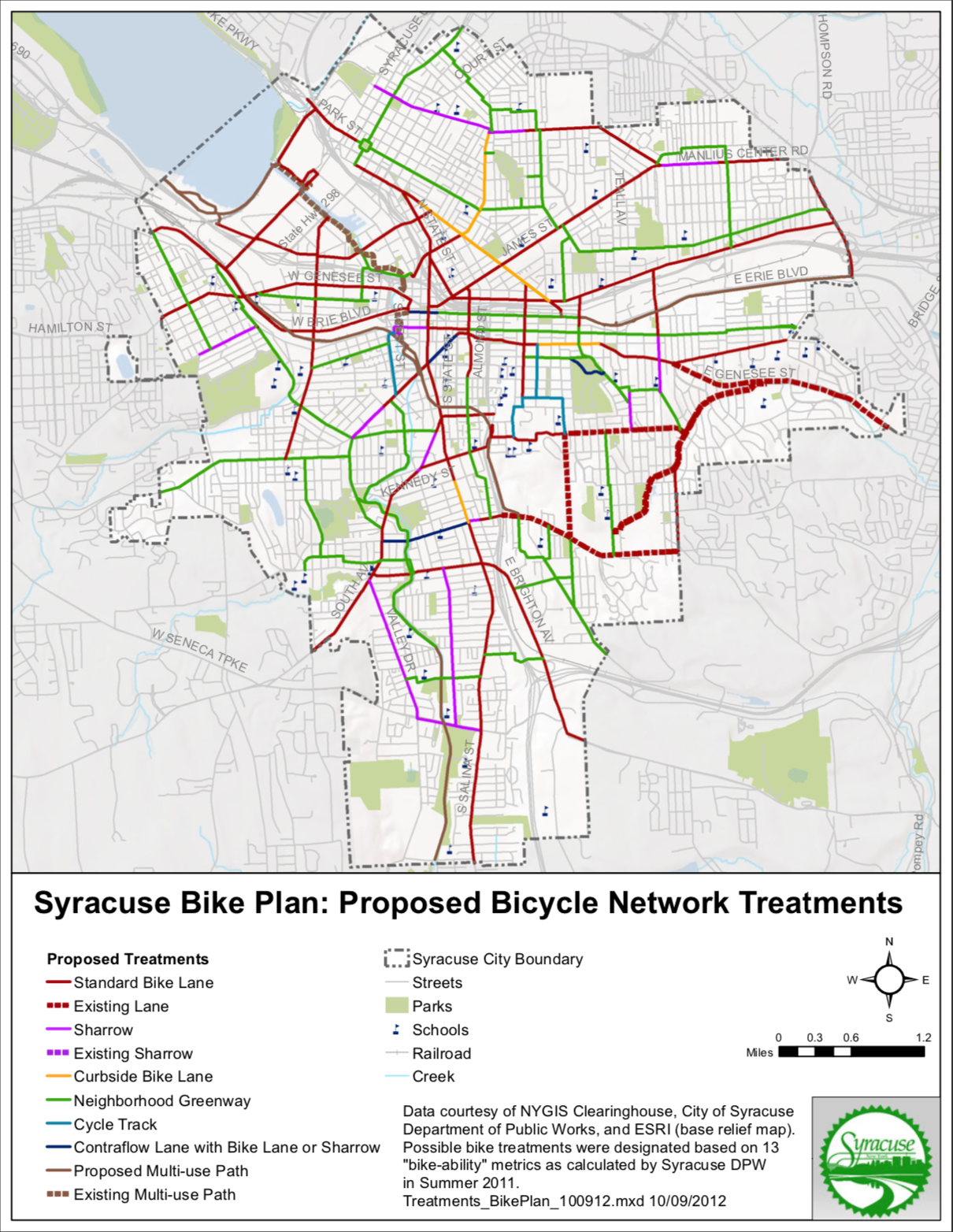

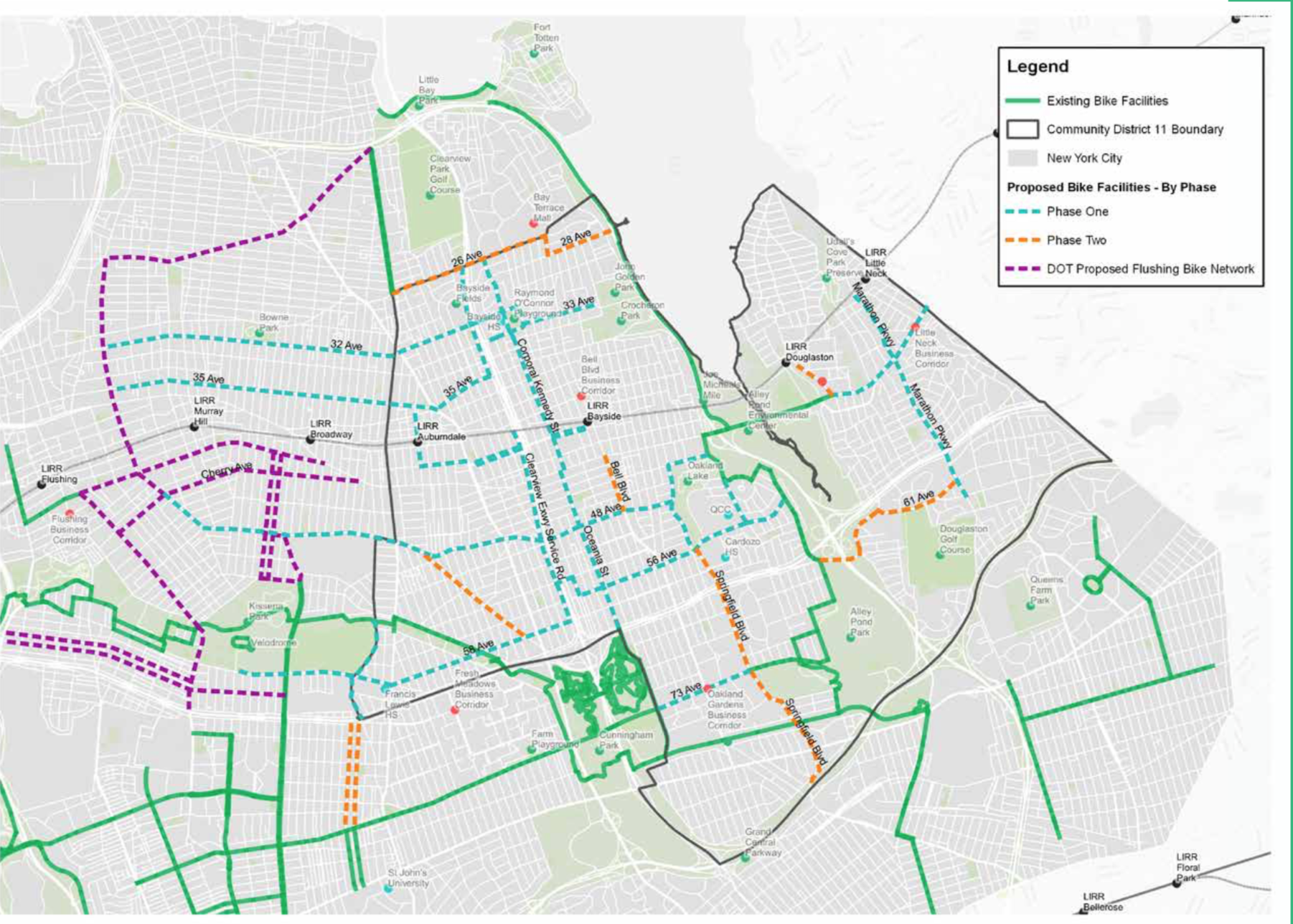

Looking at this map it quickly becomes apparent that the vast majority of space in the Downtown area is devoted to the storage of vehicles. Some will argue that this parking is needed for all of the workers, residents, and visitors that the area attracts, yet we don’t seem to have the same interest in providing this sort of access for people traveling on bike or on foot. In fact, if you look at the most recent Bike Suitability Map from SMTC you’ll notice that there are very few ways to enter Downtown safely on a bike. Crossing under highways and railroad bridges, competing with off ramps where drivers maintain their highway speeds, it is often dangerous getting into this central area. Just recently a cyclist was hit near a highway on-ramp and was sent to the hospital in critical condition.

Screenshot of the Interactive Bike Suitability Map from SMTC

There has been movement to improve access to Downtown Syracuse on bike, with the Empire State Trail and the Creek Walk both improving navigation and safety for riders and pedestrians, but there is room for improvement. Some of the infrastructure that has been built is extremely high quality, including a protected bike lane on the service road of West Street and in one direction on Water Street (although winter upkeep still needs improvement), while others leave plenty to be desired. Sharrows through Clinton Square lead to a path that’s blocked off for nearly half of the year due to the ice skating rink, while a bike path just west of the square is up on the sidewalk, forcing pedestrians and cyclists to share in already limited space. The roadway west of Clinton Square could’ve removed some parking spaces creating enough room for a protected bike path in both directions.

Improving upkeep in the winter and adding additional painted lanes around known yearly obstructions would help increase the usefulness of this trail, both to visitors and, more importantly, residents. Still, these lanes are major improvements and begin to give back some space to non-car uses.

While bike infrastructure is slowly improving, pedestrian infrastructure should not be overlooked. Downtown Syracuse has wide sidewalks that make it enjoyable to walk around with friends, with people rarely having to walk in a line behind one another as you go. Even then, there are still signs that pedestrians aren’t in control of this space.

At times sidewalks must be blocked off for various purposes, due to damage or construction, with barriers put up to prevent people from using them. Often these occur in the middle of a block, far from an intersection. Some people will cross the street quickly, or just walk in the street for a bit, which puts their well being at risk. On the other hand, disabled individuals are not provided a way to make either of those decisions. In other cities orange barriers are often rolled out to carve out a pedestrian path, allowing pedestrians to stay on the same side of the road safely, while also building temporary ramps to assist those with disabilities. Simply requiring construction crews or building owners to provide this path can help keep pedestrians safer by preventing darting across the street.

But let’s get back to parking for a moment. While parking lots dominate the downtown area, and will be discussed in more depth in a later post, parking garages serve up their own issues for pedestrians. Garages by nature utilize very compact designs, attempting to squeeze ramps and entrances in where they can while providing the most parking as possible. Due to some of these designs, sight lines when entering and exiting a garage can be reduced significantly. Some garages work to slow drivers down before they exit by placing their automatic arms closer to the opening, ensuring that the vehicles stop and have time to see. Others have no such barrier near their exits, allowing cars to quickly rush out. While most garages make use of fish-eyed mirrors to help with bad sight lines, they are only useful if the driver is moving slow enough to take in what they are showing.

One particularly bad garage is located on Warren Street (above). The garage makes use of a singular ramp for both entering and exiting, with a green light near the exit to warn incoming vehicles. As Warren Street is a one-way street, the light only faces in one direction, making it essentially useless for pedestrians coming in the other direction. The ramp’s tight fit makes it difficult to see into, and makes use of no devices to slow drivers down as they exit. Due to this, driver’s rarely have time to see whether a pedestrian is coming or not, and the pedestrian has little time to see the car approaching.

One approach that should be taken whenever a car is meant to enter a pedestrian space, such as a sidewalk, is the raise it up. Too often we make use of curb cuts, lowering the sidewalk down to meet the roadway, instead of forcing cars to come up into the pedestrian space. By forcing cars to make that movement, their speed decreases and alerts them to the fact that this is not a space meant for them. The YouTube Channel Not just Bikes has produced an excellent video on this topic (below).

Now there is much more we can do to change this dynamic. Throughout the spring I will be writing about more dramatic ideas of how to change our use of streets in Downtown Syracuse. To create change we need to stop considering how our streets and sidewalks are currently used, but instead think of what we would like to see. The minor changes discussed in this post are to help improve things immediately, along with some of my other pet peeves, but we should also think more radically about what the future should be.