For the summer of 2020 I will be releasing a series of articles reflecting on some of the things cities, and urban planners specifically, can be advocating and planning for to help in our fight against the climate crisis. These pieces will reflect on our transportation networks, the need for urban living, and protecting our natural resources while bringing them into the city. While these are not comprehensive of everything that needs to be done to turn the tide of this crisis, they will provide a different vision of what our world could be like if we commit to a different form of development.

So much of the hopes of the environmentalist movement seems to rely on the large scale adoption of electric vehicles. Transportation currently accounts for 28 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, more than any other sector of our economy, and we are currently the only major economy seeing that share increase. While electric vehicles are key to our transition away from fossil fuels, they are not a silver bullet.

First we must consider the amount of infrastructure that must be built in order to accommodate a full on switch to electric vehicles. Private vehicles will require different charging times and configurations than commercial vehicles or delivery trucks. Most personal vehicles will be able to be accommodated at your home or your place of business, but the larger vehicles may need more significant infrastructure to provide the charges necessary to propel their weight. This infrastructure is much easier to build out in urban and suburban areas where charging stations can be located within a decent range for these vehicles, but may become more difficult in long distance passages many tractor trailers use each day.

We must also consider how long it will take to switch everyone into an electric vehicle, let alone electric tractor trailers that can meet our current demands. When factoring in the average length of time cars stay on the road, it’ll be at least 15 years for our current American fleet to turn over. Ensuring that those vehicles are all electric would require a huge boost in production, taxes or regulations to push people towards purchasing electric vehicles, and a quick ramp up of the previously mentioned infrastructure needed to support this change. We must also consider the fact that the production of electric vehicles takes twice as much energy as our current internal combustion engine vehicles. While each of these facts will change as general energy production becomes cleaner, battery technology must also improve to solve some of the issues with current electric vehicles.

According to a report in The Verge, the batteries currently in use for electric vehicles remain difficult to recycle and too dangerous to dispose of in landfills, as “thermal runaway” may occur, resulting in possible explosions. Without a major ramping up of battery recycling programs, along with a redesign of batteries to make it simpler and safer to remove and replace them, electric vehicles will struggle to live up to their greener promises. We must also be concerned with non-exhaust related emissions, which are caused by the wear and tear of tires on asphalt. Replacing all vehicles with electric vehicles may even increase these forms of emissions, due to the heavier weights of the vehicles, which again requires the need to improve battery technology to lighten the load.

In his book Better Buses Better Cities, Steven Higashide references a study by the Air Resources Board in California that notes that even if every car in California switched to electric, and 75 percent of the energy grid used renewable sources, driving would still need to be decreased by over 15 percent to reach their current climate goals. A similar study was conducted in Hawaii, again finding that a switch to electric vehicles was not enough to fully remove their state’s dependence on fossil fuels. s part of this we must ensure that our transit agencies move towards all electric fleets, something that Edmonton, Canada is working towards on a large scale. Their new electric fleet was designed specifically with efficiency in mind, both in terms of charging efficiency and financial efficiency (charging stations with fewer moving parts require agencies to have fewer replacements on hand, and less risk of things going wrong.) Edmonton’s transit agency understood the need for the transition and wanted to ensure that these large scale investments were made in a responsible way. While it's difficult to require private citizens and corporations to move to all electric, requiring publicly supported agencies to make the move is far easier and helps push our urban infrastructure in the direction of an electric future.

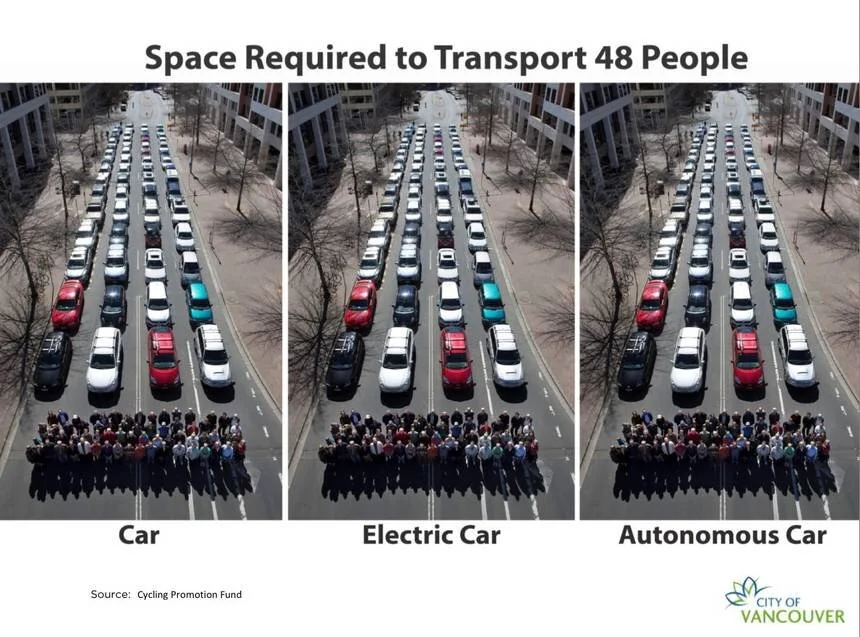

Beyond the technological challenges that must be addressed, we must also consider whether the space we currently devote to personal vehicles is healthy for cities and communities moving forward. In the image below, which has made the rounds on the internet, we start to understand that no matter what technology we develop, cars will still take up way more space to move the same amount of people than public transit or cycling infrastructure. Many will argue that autonomous vehicles will “solve congestion” but most of these scenarios assume that pedestrians won’t be around, or they’ll be penned in like animals. Anyone who envisions that as an ideal city must never have spent time in a city. People on foot are the life of cities, and everyone is a pedestrian at some point in their travels.

On the other hand, you can look to Helsinki, Finland and the recognition that we must prioritize efficiency and accessibility within cities. On their hierarchy for infrastructure investment they rank personal vehicles last in terms of importance, with an understanding that urban spaces must prioritize residents over commuters. Not only does this help create spaces for communities and neighbors, which are increasingly needed, but it also demonstrates that we have the ability to make significant progress in our climate goals without waiting for technology to improve. But even in the more liberal areas of this country, advocating against the interests of drivers faces stiff opposition. The War on Cars podcast spent an episode reflecting on this blind spot in liberal policy making, but we can also see this reflected in some of the bigger climate proposals of the last few years, who rarely, if ever, question the dominance of the personal vehicle.*

All of this is not to say we don’t need electric vehicles, and in fact we need them quickly. Requiring all new vehicles to be electric would do a great deal of good in our fight against the climate crisis, but we must also work to disincentivize driving and promote other forms of travel, including both public transit and active transit options. As we’ve seen, the space given over to private vehicles must be corrected to provide space for greener, healthier forms of transportation while reducing the amount of vehicles being produced each year, helping further curb our energy needs.

*This piece has focused on the environmental impacts of electric vehicles, but there are general safety concerns that should be considered for personal vehicles, especially with the newer obsession with SUVs and trucks, which also abide by lower emissions standards than sedans due to their classification.